More Information

Submitted: January 05, 2023 | Approved: February 13, 2023 | Published: February 14, 2023

How to cite this article: Rayamajhi K, Bansal R, Aggarwal B. Mammographic correlation with molecular subtypes of breast carcinoma. J Radiol Oncol. 2023; 7: 001-005.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jro.1001045

Copyright License: © 2023 Rayamajhi K, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Mammographic correlation with molecular subtypes of breast carcinoma

Kundana Rayamajhi1*, Richa Bansal2 and Bharat Aggarwal3

1Breast Imaging Fellow, Department of Radiology, Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India

2Principal Consultants, Max Super specialty Hospital, New Delhi, India

3HOD and Principal Consultant, Max Super specialty Hospital, New Delhi, India

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Kundana Rayamajhi, Breast Imaging Fellow, Department of Radiology, Max Super specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi, India, Email: [email protected]

Aim: To determine the correlation between mammographic features of breast cancer with molecular subtypes and to calculate the predictive value of these features.

Materials and method: This is a retrospective study of breast cancer patients presenting between January 2017 and December 2021, who underwent mammography of the breast followed by true cut biopsy and immunohistochemical staining of the tissue sample. Breast carcinoma patients without preoperative mammograms, those unable to undergo histopathological and IHC examinations and h/o prior cancer treatment were excluded. On mammography, size, shape, margins, density, the presence or absence of suspicious calcifications and associated features were noted.

Results: Irregular-shaped tumors with spiculated margins were likely to be luminal A/B subtypes of breast cancer. Tumors with a round or oval shape with circumscribed margins were highly suggestive of Triple negative breast cancer. Tumors with suspicious calcifications were likely to be HER2 enriched.

Conclusion: Mammographic features such as irregular or round shape, circumscribed or noncircumscribed margins and suspicious calcifications are strongly correlated in predicting the molecular subtypes of breast cancer and thus may further expand the role of conventional breast imaging.

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death due to cancer in women worldwide and the incidence has been increasing [1]. The molecular subtyping of breast cancer has become an essential requirement for treatment planning disease prognosis and avoiding overtreatment [2]. The St Galen International Expert Consensus recently classified breast cancer into five different molecular subtypes based on gene expression patterns: luminal A (LA), luminal B [(LB; HER2−), LB (HER2+)], human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-enriched, and basal-like (triple-negative). Pathologically, these molecular subtypes are categorized based on tumor markers’ expression status: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), HER2neu overexpression, and Ki-67 index. Invasive breast cancer with ER and/or PR positive, HER2 negative and low Ki-67 index (Ki-67 < 14%) are considered LA type, ER and/or PR positive with high Ki-67 index (Ki-67 ≥14%) and HER2 negative are LB(HER2−) subtype, ER and/or PR positive with HER2 positive are LB (HER2+) subtype, ER and PR negative with HER2neu overexpression are HER2-enriched type, and breast cancer with all three receptors (ER/PR/HER2neu) negative are basal or triple-negative type [3-8].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the gold standard for detecting hormone receptor (ER/PR), HER2 overexpression and Ki-67 expression status, but it is an invasive method, an expensive test and not readily available in many developing and underdeveloped countries.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between mammographic image features and molecular subtypes of breast carcinoma. Molecular classification by immunohistochemistry is necessary for therapeutic decision and prognosis of breast carcinoma since luminal A subtype is associated with favorable biological characteristics and a better prognosis than triple negative tumors that are associated with a poor prognosis.

This is a retrospective study conducted at Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi. The study sample consisted of 119 known cases of breast carcinoma patients presenting between January 2017 and December 2021 who were evaluated with mammography and underwent ultrasound-guided true cut biopsy followed by histopathological and IHC examination of the sample.

The clinical and pathological results and mammography reports of 119 patients were retrospectively analyzed. The mammographic appearances were assessed according to the analytical criteria of the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System from the database of Max Super Specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi.

Inclusion criteria: K/C/O breast cancer who underwent true cut biopsy with IHC staining. Equivocal HER2 neu cases followed by FISH.

Exclusion criteria: K/C/O breast carcinoma without preoperative mammograms, Patient without detailed pathological information, History of prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Prior cancer treatment and those unable to undergo histopathological and IHC examinations.

Mammography interpretation

Two standard imaging views (craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique) were used for mammography, with additional views if necessary. Using the American College of Radiology (ACR) Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon, we retrospectively examined breast density (fatty, scattered fibro glandular, heterogeneously dense, or dense) and the presence of lesions. Lesions were described as masses reporting size, shape (oval, round, or irregular) and margins (circumscribed, micro lobulated, obscured, indistinct, or spiculated); microcalcifications; masses with microcalcifications, asymmetric focal densities or architectural distortions and associated features like nipple retraction or skin thickening.

Tissue sampling and analysis

Percutaneous imaging-guided core biopsy or surgical excision was performed to acquire a tumor sample. Specimens underwent immunohistochemistry to detect the levels of ER, PR, HER2 oncogene overexpression, and Ki-67. Stained slides were evaluated for nuclear ER or PR expression according to the College of American Pathologists guidelines (≥ 1% cutoff for positive) by pathologists. Ki-67 index < 14% was considered as low expression and ≥ 14% was considered high expression. HER2 expression on IHC was based on the cell membrane staining pattern with grade 2+ considered equivocal, grade 3+ considered positive, and grade 1+ or 0 considered negative. All the equivocal samples were further analyzed with fluorescence in situ hybridization where a FISH ratio higher than 2.2 or HER2 gene copy greater than 6.0 was considered positive. Based on ER/PR/HER2 and Ki-67 expression status, breast cancers were categorized into four molecular subtypes in accordance with St. Gallen 2011 consensus surrogate definitions of the molecular subtypes:

- LA subtype: ER- and/or PR-positive, HER2-negative, and Ki-67 < 14%

- LB subtype: either ER- and/or PR-positive, HER2-negative, and Ki-67 ≥ 14% Or ER- and/or PR-positive and HER2-positive

- HER2-enriched type (HER2): ER- and PR-negative and HER2-positive Triple-negative type (TN): ER, PR, and HER2-negative [9]

- As Ki -67 was not available in all data, in our study we have kept LA and LB subtypes into one category-Luminal types. Thus, breast cancer was categorized into three molecular subtypes.

- Luminal A/B

- HER2-enriched

- Triple-negative

Statistical analysis

Our data was collected on Microsoft Office Excel 2010 and statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 20. The imaging features of different molecular subtypes were compared using univariate and multivariate analyses of data. Pearson chi-square test was used. For all the tests, statistical significance was assumed when the p value < 0.05.

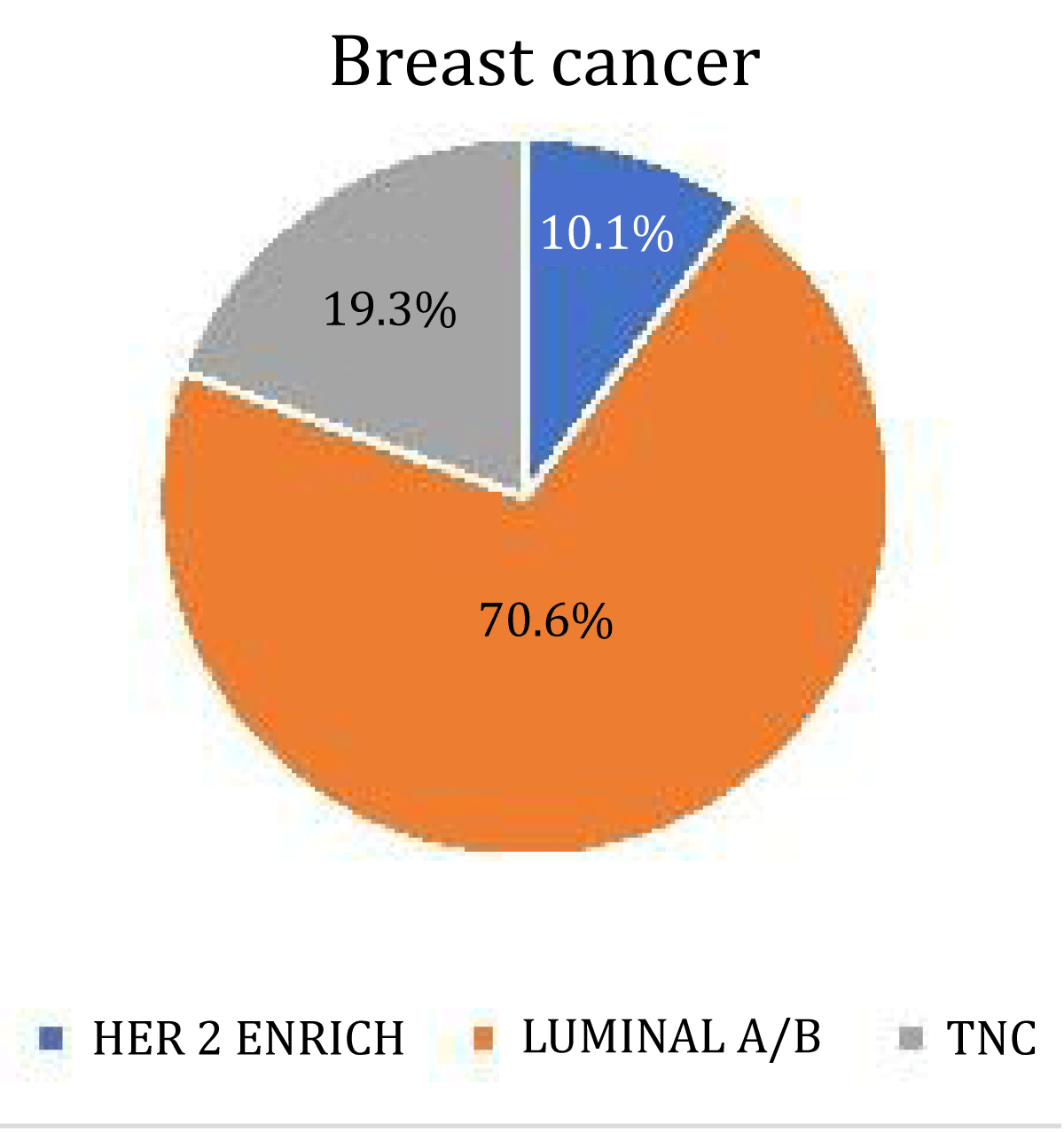

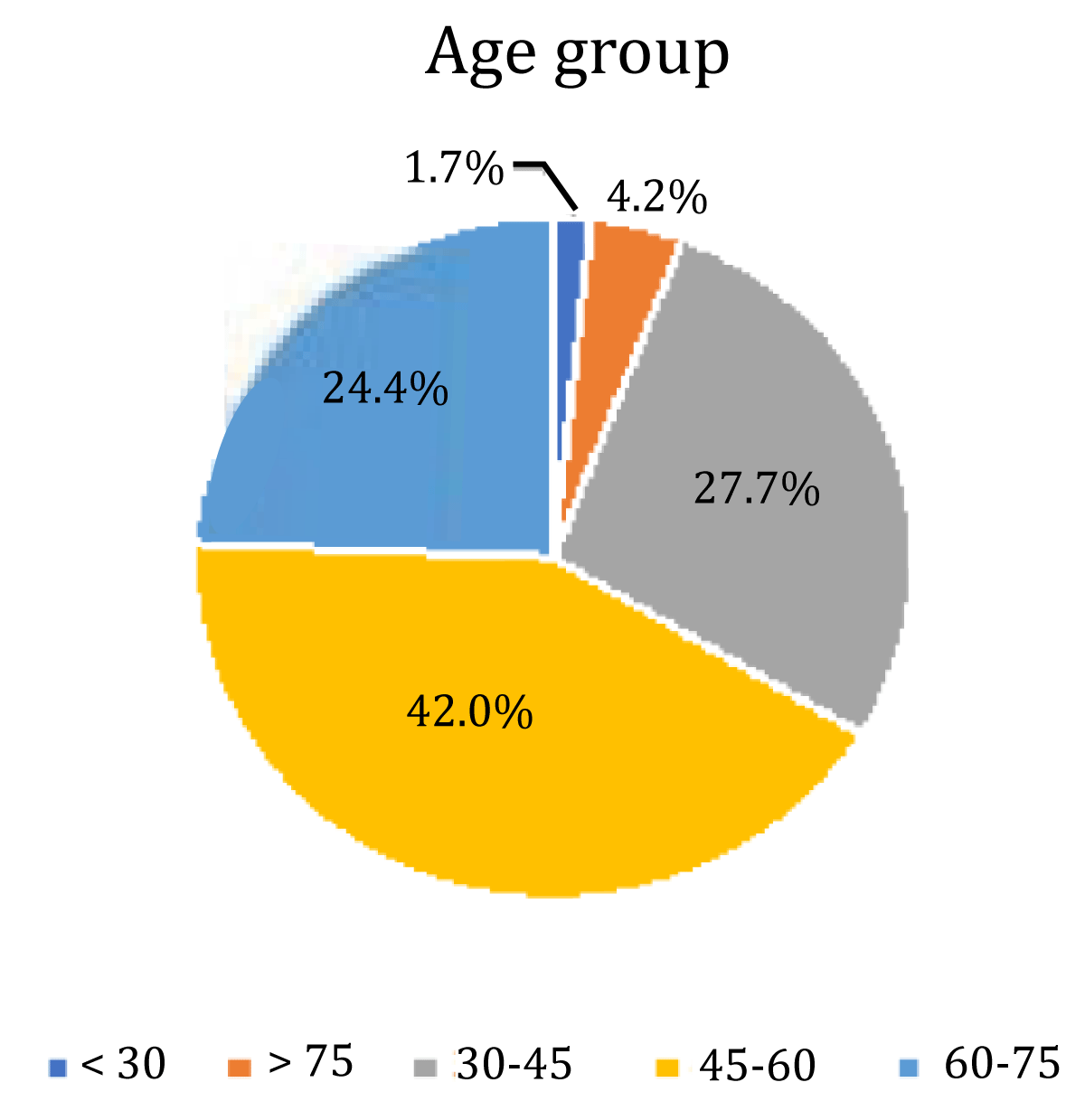

Our study consisted of 119 patients with a mean age of 53.14. Out of 119 patients, 84 (70.6%) were luminal A/B 23 were TNC (19.3%) and 12 were HER 2 enriched (10.1%) molecular subtypes. Most breast cancers had irregular shapes 84 (70.6%). The irregular shape was most common in luminal A/B types 66 (78.6%). The round or oval shape was most commonly seen in TNC 12 (52%). HER2 enrich cancer mostly had irregular shapes 7 (58.3%). There was a significant association between shape and breast cancer (p - value = 0.048).

Circumscribed margins were more common in TNC 6 (85.7%). Circumcribed margins were uncommon in luminal types 1 (1.1%) and none in Her 2 enrich 0(0). Spiculated margins were the most common margins in breast cancer patients 71 (59.7%), followed by indistinct margins 24(20.2%), micro lobulated 16(13.4%), circumscribed 7 (5.9%), and the least common was obscured margin 1 (0.8%). Spiculated margins were more commonly seen in luminal A/B 58 (81.7%) followed by TNC 8 (11.3%) and HER2 enrich 5 (7%). Indistinct margins were most common in luminal A/B 15 (62.5%) followed by TNC 6 (25%) and Her 2 enrich 3 (12.5%). Micro lobulated margins were most commonly seen in luminal A/B 9 (56.2%) followed by Her 2 enrich 4 (25%) and TNC 3 (18.8%).

There was a significant association between margins and breast cancer (p value < 0.001).

High-density masses in mammograms were the most common 74 (62.2%) of which luminal A/B was the most common molecular type 54 (73%) followed by TNC 16 (21.6%) and HER2 enrich 4 (5.4%). 42 (35.3%) of breast cancer presented as isodense masses. Isodense masses were most common in luminal types 27 (64.3%) followed by Her 2 enrich 8 (19%) and TNC 7 (16.7%). Hypodense masses were the least common 3 (2.5%). There was no significant association between density and breast cancer.

Out of 119 patients, 48 (40.3%) had calcifications. The most common type of breast cancer associated with calcifications was the HER2 enrich subtype (50%) followed by luminal A/B subtypes (42%) In TNC, calcifications were not so common (26%). The most common type of calcification seen in HER2 enrich patients was pleomorphic (41.7%). The most common type of calcification seen in Luminal A/B subtypes was pleomorphic (44.5%). There is no significant association between calcifications and breast cancer (p - value = 0.658).

Architectural distortion was seen in a small number of cases 8(6.7%) and was most common in luminal A/B 5 (62.5%)). Only 24 (20.2%) out of 119 patients had associated features among which 19 (16%) had nipple retraction and 15 (12.6%) had skin thickening. Luminal A/B was the most common type of Commented [s29]: ‘The’ Added breast cancer associated with nipple retraction 16 (84.2) and skin thickening 12 (80.0%) (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1: Pie chart showing the distribution of 3 molecular subtypes.

Figure 2: Pie chart showing means age group in different molecular subtypes.

In this study, we analyzed the associations between mammographic features with molecular subtypes of breast cancer categorized based on receptor status (ER, PR, HER2+, and Ki67) determined by IHC.

In our study, luminal A/B subtypes showed a significant positive association between having irregular shapes and spiculated margins in a mammogram (p value = 0.048 and < 0.001 respectively). These findings were similar to a study done by Anupama, et al. who reported that tumors with noncircumscribed margins had 9.5 times higher chances of having hormone receptor positivity [10]. Similarly, Celebi, et al. found that tumors with combined findings of non- circumscribed margins and posterior shadowing were found to have a 10.58 times higher association with luminal subtypes [11]. In our study, 52% of TNC were seen as round or oval, masses with circumscribed margins. TNC reportedly has associated microcalcifications less frequently than other phenotypes [12-14]. In our study, only 26% of TNC had calcifications. Our report supports previous reports where TNCs were mistaken for benign lesions due to their benign appearing features.

In our study most common type of breast cancer associated with calcifications was HER2 enrich followed by Luminal A/B. In a study done by Seo, et al. and Zhang, et al, tumors detected to have microcalcifications on mammograms were strongly associated with HER2 overexpression [15,16]. Sun, et al. reported malignant calcification to be more frequent in HER2/ neu-positive tumors [17].

Boisserie-Lacroix, et al. stated that the presence of calcifications in the mammogram may predict a HER2/neu-positive status when the HER2 score is equivocally 2+ in immunohistochemistry [18].

In our study, pleomorphic calcifications were the most common type seen in HER2 enrich subtypes. Cen, et al. and Patel, et al. also found that HER2-enriched tumors were more likely to have heterogeneous and pleomorphic microcalcifications on a mammogram [19,20]. HER 2 enrich had irregular shapes with spiculated margins.

Most breast cancers presented as high-density mass followed by isodense mass.

Also, there was no significant difference in the diagnosis of nipple retraction by mammography in 3 different subtypes (p = 0.788) which was consistent with Jiang, et al. study [21]. Architectural distortion with nipple retraction and skin thickening was most common in luminal types.

Tumor shapes, margins and the presence of suspicious calcifications on mammography can be correlated in predicting the molecular subtype of breast cancer, and thus may further expand the role of conventional breast imaging for a more precise diagnosis of breast cancer. Tumors with irregular shapes and non-circumscribed margins are predicted to be LA or LB subtypes. Tumors with suspicious calcifications are strongly predicted to be HER2 subtypes. Oval or round shape tumors with circumscribed margins with absent calcifications are predicted to be triple-negative types of breast cancer. IHC-based classification of breast tumors can be helpful since the predictive power of IHC criteria appears to be similar to that of gene expression analysis, this information can be used to improve therapeutic decisions, mainly for luminal B,HER2-overexpressing and basal-like subtypes. The luminal A subtype is associated with favorable biological characteristics and a better prognosis than triple negative tumors which is associated with a poor prognosis and unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics. Our results should be confirmed by large studies conducted in other institutions and hospitals.

Supplementary tables

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Richa Bansal and Dr. Bharat Aggarwal for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the research work. I would also like to thank the Department of Radiology Max Super specialty Hospital, Saket, New Delhi for their constant support.

- Cancer Fact Sheet World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed Oct 23, 2020.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC. 2019, GLOBOCAN 2018, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/fact-sheets-cancers. Accessed Aug 25, 2020.

- Yan K, Agrawal N, Gooi Z. Head and Neck Masses. Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;102(6):1013-1025. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.06.012. Epub 2018 Sep 20. PMID: 30342605.

- Cognetti DM, Weber RS, Lai SY. Head and neck cancer: an evolving treatment paradigm. Cancer. 2008 Oct 1;113(7 Suppl):1911-32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23654. PMID: 18798532; PMCID: PMC2751600.

- Jaffray DA, Gospodarowicz MK. Radiation Therapy for Cancer. 2015. ISBN 9781464803499.

- Shetty AV, Wong DJ. Systemic Treatment for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2017 Aug;50(4):775-782. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2017.03.013. PMID: 28755705.

- Barazzuol L, Coppes RP, van Luijk P. Prevention and treatment of radiotherapy-induced side effects. Mol Oncol. 2020 Jul;14(7):1538-1554. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12750. Epub 2020 Jun 24. PMID: 32521079; PMCID: PMC7332214.

- Gil Z, Fliss DM. Contemporary management of head and neck cancers. Isr Med Assoc J. 2009 May;11(5):296-300. PMID: 19637508.

- Deloch L, Derer A, Hartmann J, Frey B, Fietkau R, Gaipl US. Modern Radiotherapy Concepts and the Impact of Radiation on Immune Activation. Front Oncol. 2016 Jun 20;6:141. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00141. PMID: 27379203; PMCID: PMC4913083.

- Baskar R, Dai J, Wenlong N, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Biological response of cancer cells to radiation treatment. Front Mol Biosci. 2014 Nov 17;1:24. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00024. PMID: 25988165; PMCID: PMC4429645.

- Manukian G, Bar-Ad V, Lu B, Argiris A, Johnson JM. Combining Radiation and Immune Checkpoint Blockade in the Treatment of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019 Mar 6;9:122. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00122. PMID: 30895168; PMCID: PMC6414812.

- Jensen SB, Vissink A, Limesand KH, Reyland ME. Salivary Gland Hypofunction and Xerostomia in Head and Neck Radiation Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2019 Aug 1;2019(53):lgz016. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgz016. PMID: 31425600.

- Wu VWC, Leung KY. A Review on the Assessment of Radiation Induced Salivary Gland Damage After Radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2019 Oct 17;9:1090. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01090. PMID: 31750235; PMCID: PMC6843028.

- Miranda-Rius J, Brunet-Llobet L, Lahor-Soler E, Farré M. Salivary Secretory Disorders, Inducing Drugs, and Clinical Management. Int J Med Sci. 2015 Sep 22;12(10):811-24. doi: 10.7150/ijms.12912. PMID: 26516310; PMCID: PMC4615242.

- Ghannam MG, Singh P, Anatomy H , Salivary Glands N. StatPearls 2019 Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538325/. Accessed Jan 29, 2020.

- Punj A. Secretions of Human Salivary Gland. Secretions of Human Salivary Gland, Salivary Glands - New Approaches in Diagnostics and Treatment, Işıl Adadan Güvenç, IntechOpen. 2018. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.75538. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/salivary-glands-new-approaches-in-diagnostics-and-treatment/secretions-of-human-salivary-gland.

- Benn AM, Thomson WM. Saliva: an overview. N Z Dent J. 2014 Sep;110(3):92-6. PMID: 25265747.

- Tiwari M. Science behind human saliva. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011 Jan;2(1):53-8. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82322. PMID: 22470235; PMCID: PMC3312700.

- Proctor GB. The physiology of salivary secretion. Periodontol 2000. 2016 Feb;70(1):11-25. doi: 10.1111/prd.12116. PMID: 26662479.

- Qin R, Steel A, Fazel N. Oral mucosa biology and salivary biomarkers. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Sep-Oct;35(5):477-483. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.06.005. Epub 2017 Jun 27. PMID: 28916029.

- Farnaud SJ, Kosti O, Getting SJ, Renshaw D. Saliva: physiology and diagnostic potential in health and disease. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010 Mar 16;10:434-56. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.38. PMID: 20305986; PMCID: PMC5763701.

- Fábián TK, Beck A, Fejérdy P, Hermann P, Fábián G. Molecular mechanisms of taste recognition: considerations about the role of saliva. Int J Mol Sci. 2015 Mar 13;16(3):5945-74. doi: 10.3390/ijms16035945. PMID: 25782158; PMCID: PMC4394514.

- von Bültzingslöwen I, Sollecito TP, Fox PC, Daniels T, Jonsson R, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan MT, Carrozzo M, Gandera B, Fujibayashi T, Navazesh M, Rhodus NL, Schiødt M. Salivary dysfunction associated with systemic diseases: systematic review and clinical management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007 Mar;103 Suppl:S57.e1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.010. PMID: 17379156.

- Dashtipour K, Bhidayasiri R, Chen JJ, Jabbari B, Lew M, Torres-Russotto D. RimabotulinumtoxinB in sialorrhea: systematic review of clinical trials. J Clin Mov Disord. 2017 Jun 6;4:9. doi: 10.1186/s40734-017-0055-1. PMID: 28593050; PMCID: PMC5460542.

- Jost WH, Friedman A, Michel O, Oehlwein C, Slawek J, Bogucki A, Ochudlo S, Banach M, Pagan F, Flatau-Baqué B, Dorsch U, Csikós J, Blitzer A. Long-term incobotulinumtoxinA treatment for chronic sialorrhea: Efficacy and safety over 64 weeks. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020 Jan;70:23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.11.024. Epub 2019 Nov 26. PMID: 31794936.

- Frydrych AM. Dry mouth: Xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction. Aust Fam Physician. 2016 Jul;45(7):488-92. PMID: 27610431.

- Azuma N, Katada Y, Kitano S, Sekiguchi M, Kitano M, Nishioka A, Hashimoto N, Matsui K, Iwasaki T, Sano H. Correlation between salivary epidermal growth factor levels and refractory intraoral manifestations in patients with Sjögren's syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2014 Jul;24(4):626-32. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2013.850766. Epub 2013 Nov 5. PMID: 24252043.

- Millsop JW, Wang EA, Fazel N. Etiology, evaluation, and management of xerostomia. Clin Dermatol. 2017 Sep-Oct;35(5):468-476. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.06.010. Epub 2017 Jun 27. PMID: 28916028.

- Tan ECK, Lexomboon D, Sandborgh-Englund G, Haasum Y, Johnell K. Medications That Cause Dry Mouth As an Adverse Effect in Older People: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Jan;66(1):76-84. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15151. Epub 2017 Oct 26. PMID: 29071719.

- Vissink A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ, Limesand KH, Jensen SB, Fox PC, Elting LS, Langendijk JA, Coppes RP, Reyland ME. Clinical management of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients: successes and barriers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Nov 15;78(4):983-91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.052. PMID: 20970030; PMCID: PMC2964345.

- Schaue D, Kachikwu EL, McBride WH. Cytokines in radiobiological responses: a review. Radiat Res. 2012 Dec;178(6):505-23. doi: 10.1667/RR3031.1. Epub 2012 Oct 29. PMID: 23106210; PMCID: PMC3723384.

- Williams JP, McBride WH. After the bomb drops: a new look at radiation-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Int J Radiat Biol. 2011 Aug;87(8):851-68. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2011.560996. Epub 2011 Mar 21. PMID: 21417595; PMCID: PMC3314299.

- Mohammadi N, Seyyednejhad F, Alizadeh Oskoee P, Savadi Oskoee S, Mofidi N. Evaluation of Radiation-induced Xerostomia in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinomas. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2007 Summer;1(2):65-70. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2007.011. Epub 2007 Sep 10. PMID: 23277836; PMCID: PMC3525927.

- Strojan P, Hutcheson KA, Eisbruch A, Beitler JJ, Langendijk JA, Lee AWM, Corry J, Mendenhall WM, Smee R, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Treatment of late sequelae after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017 Sep;59:79-92. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.07.003. Epub 2017 Jul 18. PMID: 28759822; PMCID: PMC5902026.

- Franzén L, Funegård U, Ericson T, Henriksson R. Parotid gland function during and following radiotherapy of malignancies in the head and neck. A consecutive study of salivary flow and patient discomfort. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28(2-3):457-62. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80076-0. PMID: 1591063.

- Siddiqui F, Movsas B. Management of Radiation Toxicity in Head and Neck Cancers. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2017 Oct;27(4):340-349. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2017.04.008. PMID: 28865517.

- Berk LB, Shivnani AT, Small W Jr. Pathophysiology and management of radiation-induced xerostomia. J Support Oncol. 2005 May-Jun;3(3):191-200. PMID: 15915820.

- Hammerlid E, Silander E, Hörnestam L, Sullivan M. Health-related quality of life three years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer--a longitudinal study. Head Neck. 2001 Feb;23(2):113-25. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<113::aid-hed1006>3.0.co;2-w. PMID: 11303628.

- Hall SC, Hassis ME, Williams KE, Albertolle ME, Prakobphol A, Dykstra AB, Laurance M, Ona K, Niles RK, Prasad N, Gormley M, Shiboski C, Criswell LA, Witkowska HE, Fisher SJ. Alterations in the Salivary Proteome and N-Glycome of Sjögren's Syndrome Patients. J Proteome Res. 2017 Apr 7;16(4):1693-1705. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b01051. Epub 2017 Mar 24. PMID: 28282148; PMCID: PMC9668345.

- Jehmlich N, Stegmaier P, Golatowski C, Salazar MG, Rischke C, Henke M, Völker U. Differences in the whole saliva baseline proteome profile associated with development of oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Proteomics. 2015 Jul 1;125:98-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.04.030. Epub 2015 May 19. PMID: 25997676.

- Thomson WM. Dry mouth and older people. Aust Dent J. 2015 Mar;60 Suppl 1:54-63. doi: 10.1111/adj.12284. PMID: 25762042.

- Cereda E, Cappello S, Colombo S, Klersy C, Imarisio I, Turri A, Caraccia M, Borioli V, Monaco T, Benazzo M, Pedrazzoli P, Corbella F, Caccialanza R. Nutritional counseling with or without systematic use of oral nutritional supplements in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2018 Jan;126(1):81-88. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.10.015. Epub 2017 Oct 27. PMID: 29111172.

- Li Y, Taylor JM, Ten Haken RK, Eisbruch A. The impact of dose on parotid salivary recovery in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Mar 1;67(3):660-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.021. Epub 2006 Dec 4. PMID: 17141973; PMCID: PMC2001308.

- Jiang N, Zhao Y, Jansson H, Chen X, Mårtensson J. Experiences of xerostomia after radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2018 Jan;27(1-2):e100-e108. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13879. Epub 2017 Jul 5. PMID: 28514511.

- Wang W, Xiong W, Wan J, Sun X, Xu H, Yang X. The decrease of PAMAM dendrimer-induced cytotoxicity by PEGylation via attenuation of oxidative stress. Nanotechnology. 2009 Mar 11;20(10):105103. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/10/105103. Epub 2009 Feb 16. PMID: 19417510.

- Nadig SD, Ashwathappa DT, Manjunath M, Krishna S, Annaji AG, Shivaprakash PK. A relationship between salivary flow rates and Candida counts in patients with xerostomia. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017 May-Aug;21(2):316. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_231_16. PMID: 28932047; PMCID: PMC5596688.

- Kagami H, Wang S, Hai B. Restoring the function of salivary glands. Oral Dis. 2008 Jan;14(1):15-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01339.x. PMID: 18173444.

- Villa A, Abati S. Risk factors and symptoms associated with xerostomia: a cross-sectional study. Aust Dent J. 2011 Sep;56(3):290-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01347.x. PMID: 21884145.

- Bressan V, Bagnasco A, Aleo G, Catania G, Zanini MP, Timmins F, Sasso L. The life experience of nutrition impact symptoms during treatment for head and neck cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Support Care Cancer. 2017 May;25(5):1699-1712. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3618-7. Epub 2017 Feb 15. PMID: 28204992.

- Grundmann O, Mitchell GC, Limesand KH. Sensitivity of salivary glands to radiation: from animal models to therapies. J Dent Res. 2009 Oct;88(10):894-903. doi: 10.1177/0022034509343143. PMID: 19783796; PMCID: PMC2882712.

- de Castro G Jr, Guindalini RS. Supportive care in head and neck oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010 May;22(3):221-5. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833818ff. PMID: 20186057.

- Gu J, Zhu S, Li X, Wu H, Li Y, Hua F. Effect of amifostine in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014 May 2;9(5):e95968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095968. PMID: 24788761; PMCID: PMC4008569.

- Riley P, Glenny AM, Hua F, Worthington HV. Pharmacological interventions for preventing dry mouth and salivary gland dysfunction following radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 31;7(7):CD012744. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012744. PMID: 28759701; PMCID: PMC6483146.

- Hensley ML, Hagerty KL, Kewalramani T, Green DM, Meropol NJ, Wasserman TH, Cohen GI, Emami B, Gradishar WJ, Mitchell RB, Thigpen JT, Trotti A 3rd, von Hoff D, Schuchter LM. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008 clinical practice guideline update: use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy protectants. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27(1):127-45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2627. Epub 2008 Nov 17. PMID: 19018081.

- Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, Burlage FR, Coppes RP. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(3):199-212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. PMID: 12799323.

- Braam PM, Terhaard CH, Roesink JM, Raaijmakers CP. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy significantly reduces xerostomia compared with conventional radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Nov 15;66(4):975-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.045. Epub 2006 Sep 11. PMID: 16965864.

- Teng F, Fan W, Luo Y, Ju Z, Gong H, Ge R, Tong F, Zhang X, Ma L. Reducing Xerostomia by Comprehensive Protection of Salivary Glands in Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy with Helical Tomotherapy Technique for Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jul 14;2019:2401743. doi: 10.1155/2019/2401743. PMID: 31380414; PMCID: PMC6662416.

- Marzouki HZ, Elkhalidy Y, Jha N, Scrimger R, Debenham BJ, Harris JR, O'Connell DA, Seikaly H. Modification of the submandibular gland transfer procedure. Laryngoscope. 2016 Nov;126(11):2492-2496. doi: 10.1002/lary.26029. Epub 2016 May 12. PMID: 27171786.

- Rao AD, Coquia S, De Jong R, Gourin C, Page B, Latronico D, Dah S, Su L, Clarke S, Schultz J, Rosati LM, Fakhry C, Wong J, DeWeese TL, Quon H, Ding K, Kiess A. Effects of biodegradable hydrogel spacer injection on contralateral submandibular gland sparing in radiotherapy for head and neck cancers. Radiother Oncol. 2018 Jan;126(1):96-99. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.09.017. Epub 2017 Oct 3. PMID: 28985953.

- Ho J, Firmalino MV, Anbarani AG, Takesh T, Epstein J, Wilder-Smith P. Effects of A Novel Disc Formulation on Dry Mouth Symptoms and Enamel Remineralization in Patients With Hyposalivation: An In Vivo Study. Dentistry (Sunnyvale). 2017 Feb;7(2):411. doi: 10.4172/2161-1122.1000411. Epub 2017 Feb 13. PMID: 28713645; PMCID: PMC5505684.

- Ogawa M, Oshima M, Imamura A, Sekine Y, Ishida K, Yamashita K, Nakajima K, Hirayama M, Tachikawa T, Tsuji T. Functional salivary gland regeneration by transplantation of a bioengineered organ germ. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2498. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3498. PMID: 24084982; PMCID: PMC3806330.

- Zhang NN, Huang GL, Han QB, Hu X, Yi J, Yao L, He Y. Functional regeneration of irradiated salivary glands with human amniotic epithelial cells transplantation. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013 Sep 15;6(10):2039-47. PMID: 24133581; PMCID: PMC3796225.

- Okazaki Y, Kagami H, Hattori T, Hishida S, Shigetomi T, Ueda M. Acceleration of rat salivary gland tissue repair by basic fibroblast growth factor. Arch Oral Biol. 2000 Oct;45(10):911-9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00035-2. PMID: 10973565.

- Michalopoulou F, Petraki C, Philippou A, Analitis A, Msaouel P, Koutsilieris M. Expression of IGF-IEc Isoform in Renal Cell Carcinoma Tissues. Anticancer Res. 2020 Nov;40(11):6213-6219. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14641. PMID: 33109558.

- Tran D, Bergholz J, Zhang H, He H, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li Q, Kirkland JL, Xiao ZX. Insulin-like growth factor-1 regulates the SIRT1-p53 pathway in cellular senescence. Aging Cell. 2014 Aug;13(4):669-78. doi: 10.1111/acel.12219. Epub 2014 Apr 30. PMID: 25070626; PMCID: PMC4118446.

- Xiao N, Lin Y, Cao H, Sirjani D, Giaccia AJ, Koong AC, Kong CS, Diehn M, Le QT. Neurotrophic factor GDNF promotes survival of salivary stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2014 Aug;124(8):3364-77. doi: 10.1172/JCI74096. Epub 2014 Jul 18. PMID: 25036711; PMCID: PMC4109543.

- Swick A, Kimple RJ. Wetting the whistle: neurotropic factor improves salivary function. J Clin Invest. 2014 Aug;124(8):3282-4. doi: 10.1172/JCI77194. Epub 2014 Jul 18. PMID: 25036702; PMCID: PMC4109536.

- Kojima T, Kanemaru S, Hirano S, Tateya I, Suehiro A, Kitani Y, Kishimoto Y, Ohno S, Nakamura T, Ito J. The protective efficacy of basic fibroblast growth factor in radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction in mice. Laryngoscope. 2011 Sep;121(9):1870-5. doi: 10.1002/lary.21873. Epub 2011 Aug 16. PMID: 22024837.

- Thula TT, Schultz G, Tran-Son-Tay R, Batich C. Effects of EGF and bFGF on irradiated parotid glands. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005 May;33(5):685-95. doi: 10.1007/s10956-005-1853-z. PMID: 15981868.

- Borges L, Rex KL, Chen JN, Wei P, Kaufman S, Scully S, Pretorius JK, Farrell CL. A protective role for keratinocyte growth factor in a murine model of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced mucositis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006 Sep 1;66(1):254-62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.05.025. PMID: 16904525.

- Lombaert IM, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Kampinga HH, de Haan G, Coppes RP. Keratinocyte growth factor prevents radiation damage to salivary glands by expansion of the stem/progenitor pool. Stem Cells. 2008 Oct;26(10):2595-601. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1034. Epub 2008 Jul 31. PMID: 18669914.

- Choi JS, Shin HS, An HY, Kim YM, Lim JY. Radioprotective effects of Keratinocyte Growth Factor-1 against irradiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction. Oncotarget. 2017 Feb 21;8(8):13496-13508. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14583. PMID: 28086221; PMCID: PMC5355115.

- Meyer S, Chibly AM, Burd R, Limesand KH. Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1-Mediated DNA Repair in Irradiated Salivary Glands Is Sirtuin-1 Dependent. J Dent Res. 2017 Feb;96(2):225-232. doi: 10.1177/0022034516677529. Epub 2016 Nov 16. PMID: 28106504; PMCID: PMC5331616.

- Grundmann O, Fillinger JL, Victory KR, Burd R, Limesand KH. Restoration of radiation therapy-induced salivary gland dysfunction in mice by post therapy IGF-1 administration. BMC Cancer. 2010 Aug 10;10:417. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-417. PMID: 20698985; PMCID: PMC3087323.

- Baum BJ, Zheng C, Cotrim AP, Goldsmith CM, Atkinson JC, Brahim JS, Chiorini JA, Voutetakis A, Leakan RA, Van Waes C, Mitchell JB, Delporte C, Wang S, Kaminsky SM, Illei GG. Transfer of the AQP1 cDNA for the correction of radiation-induced salivary hypofunction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006 Aug;1758(8):1071-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.11.006. Epub 2005 Dec 5. PMID: 16368071.

- Redman RS. On approaches to the functional restoration of salivary glands damaged by radiation therapy for head and neck cancer, with a review of related aspects of salivary gland morphology and development. Biotech Histochem. 2008 Jun;83(3-4):103-30. doi: 10.1080/10520290802374683. PMID: 18828044; PMCID: PMC2740375.

- Cotrim AP, Sowers A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Prevention of irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction by microvessel protection in mouse salivary glands. Mol Ther. 2007 Dec;15(12):2101-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300296. Epub 2007 Aug 28. PMID: 17726456.

- Guo L, Gao R, Xu J, Jin L, Cotrim AP, Yan X, Zheng C, Goldsmith CM, Shan Z, Hai B, Zhou J, Zhang C, Baum BJ, Wang S. AdLTR2EF1α-FGF2-mediated prevention of fractionated irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction in swine. Gene Ther. 2014 Oct;21(10):866-73. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.63. Epub 2014 Jul 17. PMID: 25030610.

- Wang JF, Liu C, Zhang Q, Huang GH. Research progress in the radioprotective effect of the canonical Wnt pathway. Cancer Biol Med. 2013 Jun;10(2):61-71. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2013.02.001. PMID: 23882420; PMCID: PMC3719192.

- Vidya Priyadarsini R, Senthil Murugan R, Nagini S. Aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway contributes to the sequential progression of DMBA-induced HBP carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2012 Jan;48(1):33-9. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.08.008. Epub 2011 Sep 15. PMID: 21924667.

- Huang J, Qu Q, Guo Y, Xiang Y, Feng D. Tankyrases/β-catenin Signaling Pathway as an Anti-proliferation and Anti-metastatic Target in Hepatocarcinoma Cell Lines. J Cancer. 2020 Jan 1;11(2):432-440. doi: 10.7150/jca.30976. PMID: 31897238; PMCID: PMC6930431.

- Orme MH, Giannini AL, Vivanco MD, Kypta RM. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 and Axin function in a beta-catenin-independent pathway that regulates neurite outgrowth in neuroblastoma cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003 Nov;24(3):673-86. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00229-x. PMID: 14664817.

- Garan A, Akyüz S, Oztürk LK, Yarat A. Salivary parameters and caries indices in children with black tooth stains. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2012 Spring;36(3):285-8. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.36.3.21466m672t723713. PMID: 22838232.

- Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell. 2017 Jun 1;169(6):985-999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. PMID: 28575679.

- Huang H, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: new (and old) players and new insights. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008 Apr;20(2):119-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.009. Epub 2008 Mar 12. PMID: 18339531; PMCID: PMC2390924.

- Song G, Ouyang G, Bao S. The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J Cell Mol Med. 2005 Jan-Mar;9(1):59-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00337.x. PMID: 15784165; PMCID: PMC6741304.

- Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003 Apr 1;116(Pt 7):1175-86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. PMID: 12615961; PMCID: PMC3006448.

- Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995 Dec 21-28;378(6559):785-9. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. PMID: 8524413.

- Krasilnikov MA. Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase dependent pathways: the role in control of cell growth, survival, and malignant transformation. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2000 Jan;65(1):59-67. PMID: 10702641.

- Huang L, Fu L. Mechanisms of resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015 Sep;5(5):390-401. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.001. Epub 2015 Jul 26. PMID: 26579470; PMCID: PMC4629442.

- Torres MA, Eldar-Finkelman H, Krebs EG, Moon RT. Regulation of ribosomal S6 protein kinase-p90(rsk), glycogen synthase kinase 3, and beta-catenin in early Xenopus development. Mol Cell Biol. 1999 Feb;19(2):1427-37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.2.1427. PMID: 9891076; PMCID: PMC116071.

- Dailey L, Ambrosetti D, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005 Apr;16(2):233-47. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.007. Epub 2005 Mar 5. PMID: 15863038.

- Alcaraz E, Vilardell J, Borgo C, Sarró E, Plana M, Marin O, Pinna LA, Bayascas JR, Meseguer A, Salvi M, Itarte E, Ruzzene M. Effects of CK2β subunit down-regulation on Akt signalling in HK-2 renal cells. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 7;15(1):e0227340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227340. PMID: 31910234; PMCID: PMC6946142.

- Kennedy SG, Wagner AJ, Conzen SD, Jordán J, Bellacosa A, Tsichlis PN, Hay N. The PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway delivers an anti-apoptotic signal. Genes Dev. 1997 Mar 15;11(6):701-13. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.701. PMID: 9087425.

- Hakim SG, Ribbat J, Berndt A, Richter P, Kosmehl H, Benedek GA, Jacobsen HC, Trenkle T, Sieg P, Rades D. Expression of Wnt-1, TGF-β and related cell-cell adhesion components following radiotherapy in salivary glands of patients with manifested radiogenic xerostomia. Radiother Oncol. 2011 Oct;101(1):93-9. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.07.032. Epub 2011 Aug 30. PMID: 21885141.

- Hai B, Yang Z, Shangguan L, Zhao Y, Boyer A, Liu F. Concurrent transient activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway prevents radiation damage to salivary glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 May 1;83(1):e109-16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.062. Epub 2012 Feb 16. PMID: 22342093; PMCID: PMC3340568.

- Haidar ZS. Bio-Inspired/-Functional Colloidal Core-Shell Polymeric-Based NanoSystems: Technology Promise in Tissue Engineering, Bioimaging and NanoMedicine. Polymers . 2010; 2: 323-352. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym2030323.

- Riley P, Glenny AM, Hua F, Worthington HV. Pharmacological interventions for preventing dry mouth and salivary gland dysfunction following radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 31;7(7):CD012744. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012744. PMID: 28759701; PMCID: PMC6483146.

- Ocampo J, Vásquez B, Sandoval C, Navarrete J, Haidar ZS, Olate, S. Características Morfocuantitativas de la Glándula Submandibular de Ratón (Mus musculus)/ Morphocuantitative Characteristics of the Mouse (Mus musculus) Submandibular Gland. International Journal of Morphology. 2020; 38: 570-577. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022020000300570.

- Ocampo J, Olate S, Haidar ZS, Vásquez B, Hiposialia y .Xerostomía Post Irradiación: Terapias Innovadoras en el Campo Biomolecular/Hyposialia and Xerostomy Post Irradiation: Innovative Therapies in the Biomolecular Field. International Journal of Morphology 2019; 37: 1564-1571. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022019000401564.

- Arany S, Xu Q, Hernady E, Benoit DS, Dewhurst W, Ovitt S, C. E. Pro-apoptotic gene knockdown mediated by nanocomplexed siRNA reduces radiation damage in primary salivary gland cultures. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012; 113, 1955–65, doi:10.1002/jcb.24064.

- Yoon YJ, Shin HS, Lim JY. A hepatocyte growth factor/MET-induced antiapoptotic pathway protects against radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction. Radiother Oncol. 2019 Sep;138:9-16. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.05.012. Epub 2019 May 25. PMID: 31136962.

- Tai G, Zhang H, Du J, Chen G, Huang J, Yu J, Cai J, Liu F. TIGAR overexpression diminishes radiosensitivity of parotid gland fibroblast cells and inhibits IR-induced cell autophagy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015 May 1;8(5):4823-9. PMID: 26191173; PMCID: PMC4503045.

- Wie SM, Wellberg E, Karam SD, Reyland ME. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Protect the Salivary Gland from Radiation Damage by Inhibiting Activation of Protein Kinase C-δ. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017 Sep;16(9):1989-1998. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0267. Epub 2017 Jun 21. PMID: 28637715; PMCID: PMC5587414.

- Choi JS, An HY, Shin HS, Kim YM, Lim JY. Enhanced tissue remodelling efficacy of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells using injectable matrices in radiation-damaged salivary gland model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018 Feb;12(2):e695-e706. doi: 10.1002/term.2352. Epub 2017 May 7. PMID: 27860388.

- Zeidan YH, Xiao N, Cao H, Kong C, Le QT, Sirjani D. Botulinum Toxin Confers Radioprotection in Murine Salivary Glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016 Apr 1;94(5):1190-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.371. Epub 2015 Dec 29. PMID: 26907915; PMCID: PMC4839970.

- An HY, Shin HS, Choi JS, Kim HJ, Lim JY, Kim YM. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome Modulated in Hypoxia for Remodeling of Radiation-Induced Salivary Gland Damage. PLoS One. 2015 Nov 3;10(11):e0141862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141862. PMID: 26529411; PMCID: PMC4631328.

- Xu L, Yang X, Cai J, Ma J, Cheng H, Zhao K, Yang L, Cao Y, Qin Q, Zhang C, Zhang Q, Sun X. Resveratrol attenuates radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction in mice. Laryngoscope. 2013 Nov;123(11):E23-9. doi: 10.1002/lary.24276. Epub 2013 Jul 12. PMID: 23794219.

- Okumura H, Nasu M, Yosue T. Effects of amifostine administration prior to irradiation to the submandibular gland in mice: autoradiographic study using 3H-leucine. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2009 Feb;85(4):151-60. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.85.151. PMID: 19408584.

- Cotrim AP, Sowers A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Prevention of irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction by microvessel protection in mouse salivary glands. Mol Ther. 2007 Dec;15(12):2101-6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300296. Epub 2007 Aug 28. PMID: 17726456.

- Cotrim AP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Sowers AL, Cook JA, Baum BJ, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Differential radiation protection of salivary glands versus tumor by Tempol with accompanying tissue assessment of Tempol by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Aug 15;13(16):4928-33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0662. PMID: 17699873.

- Cotrim AP, Sowers AL, Lodde BM, Vitolo JM, Kingman A, Russo A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. Kinetics of tempol for prevention of xerostomia following head and neck irradiation in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Oct 15;11(20):7564-8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0958. PMID: 16243832.

- Aonuma M, Nasu M, Iwata H, Yosue T. Radioprotection of the murine submandibular gland by isoproterenol: autoradiography study with 3H-leucine. Odontology. 2004 Sep;92(1):14-21. doi: 10.1007/s10266-004-0032-7. PMID: 15490300.

- Vitolo JM, Cotrim AP, Sowers AL, Russo A, Wellner RB, Pillemer SR, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ. The stable nitroxide tempol facilitates salivary gland protection during head and neck irradiation in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 1;10(5):1807-12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0194. PMID: 15014035.

- Rasey JS, Krohn KA, Menard TW, Spence AM. Comparative biodistribution and radioprotection studies with three radioprotective drugs in mouse tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986 Aug;12(8):1487-90. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(86)90200-2. PMID: 3019965.

- Rasey JS, Nelson NJ, Mahler P, Anderson K, Krohn KA, Menard T. Radioprotection of normal tissues against gamma rays and cyclotron neutrons with WR-2721: LD50 studies and 35S-WR-2721 biodistribution. Radiat Res. 1984 Mar;97(3):598-607. PMID: 6328565.

- Varghese JJ, Schmale IL, Mickelsen D, Hansen ME, Newlands SD, Benoit DSW, Korshunov VA, Ovitt CE. Localized Delivery of Amifostine Enhances Salivary Gland Radioprotection. J Dent Res. 2018 Oct;97(11):1252-1259. doi: 10.1177/0022034518767408. Epub 2018 Apr 10. Erratum in: J Dent Res. 2018 Aug;97(9):1070. PMID: 29634396; PMCID: PMC6151913.

- Shin HS, Lee S, Kim YM, Lim JY. Hypoxia-Activated Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevents Irradiation-Induced Salivary Hypofunction by Enhanced Paracrine Effect Through Fibroblast Growth Factor 10. Stem Cells. 2018 Jul;36(7):1020-1032. doi: 10.1002/stem.2818. Epub 2018 Apr 10. PMID: 29569790.

- Toshkov IA, Gleiberman AS, Mett VL, Hutson AD, Singh AK, Gudkov AV, Burdelya LG. Mitigation of Radiation-Induced Epithelial Damage by the TLR5 Agonist Entolimod in a Mouse Model of Fractionated Head and Neck Irradiation. Radiat Res. 2017 May;187(5):570-580. doi: 10.1667/RR14514.1. Epub 2017 Mar 21. PMID: 28323577; PMCID: PMC5541767.

- Xu L, Yang X, Chen J, Ge X, Qin Q, Zhu H, Zhang C, Sun X. Simvastatin attenuates radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction in mice. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016 Jul 13;10:2271-8. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S105809. PMID: 27471375; PMCID: PMC4948692.

- Crescenti EJ, Medina VA, Croci M, Sambuco LA, Prestifilippo JP, Elverdin JC, Bergoc RM, Rivera ES. Radioprotection of sensitive rat tissues by oligoelements Se, Zn, Mn plus Lachesis muta venom. J Radiat Res. 2011;52(5):557-67. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11031. PMID: 21952314.

- Coppes RP, Vissink A, Zeilstra LJ, Konings AW. Muscarinic receptor stimulation increases tolerance of rat salivary gland function to radiation damage. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997 Nov;72(5):615-25. doi: 10.1080/095530097143112. PMID: 9374441.

- Coppes RP, Zeilstra LJ, Vissink A, Konings AW. Sialogogue-related radioprotection of salivary gland function: the degranulation concept revisited. Radiat Res. 1997 Sep;148(3):240-7. PMID: 9291355.

- Menard TW, Izutsu KT, Ensign WY, Keller PJ, Morton TH, Truelove EL. Radioprotection by WR-2721 of gamma-irradiated rat parotid gland: effect on gland weight and secretion at 8-10 days post irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984 Sep;10(9):1555-9. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90502-9. PMID: 6090361.

- Sodicoff M, Conger AD. Radioprotection of the rat parotid gland by cAMP. Radiat Res. 1983 Oct;96(1):90-4. PMID: 6312484.

- Sodicoff M, Conger AD. Radioprotection of the rat parotid gland by WR-2721 and isoproterenol and its modification by propranolol. Radiat Res. 1983 Apr;94(1):97-104. PMID: 6304806.

- Pratt NE, Sodicoff M, Liss J, Davis M, Sinesi M. Radioprotection of the rat parotid gland by WR-2721: morphology at 60 days post-irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980 Apr;6(4):431-5. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90056-5. PMID: 6248498.

- Sodicoff M, Conger AD, Pratt NE, Trepper P. Radioprotection by WR-2721 against long-term chronic damage to the rat parotid gland. Radiat Res. 1978 Oct;76(1):172-9. PMID: 216048.

- Abedi SM, Yarmand F, Motallebnejad M, Seyedmajidi M, Moslemi D, Bijani A, Hosseinimehr SJ. Radioprotective Effect of Thymol Against Salivary Glands Dysfunction Induced by Ionizing Radiation in Rats. Iran J Pharm Res. 2016 Fall;15(4):861-866. PMID: 28243283; PMCID: PMC5316265.

- Palaniyandi S, Odaka Y, Green W, Abreo F, Caldito G, De Benedetti A, Sunavala-Dossabhoy G. Adenoviral delivery of Tousled kinase for the protection of salivary glands against ionizing radiation damage. Gene Ther. 2011 Mar;18(3):275-82. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.142. Epub 2010 Nov 4. PMID: 21048794.

- Timiri Shanmugam PS, Dayton RD, Palaniyandi S, Abreo F, Caldito G, Klein RL, Sunavala-Dossabhoy G. Recombinant AAV9-TLK1B administration ameliorates fractionated radiation-induced xerostomia. Hum Gene Ther. 2013 Jun;24(6):604-12. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.235. PMID: 23614651; PMCID: PMC3689188.

- Hakim SG, Benedek GA, Su YX, Jacobsen HC, Klinger M, Dendorfer A, Hemmelmann C, Meller B, Nadrowitz R, Rades D, Sieg P. Radioprotective effect of lidocaine on function and ultrastructure of salivary glands receiving fractionated radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 Mar 15;82(4):e623-30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.017. Epub 2012 Jan 13. PMID: 22245203.

- Hakim SG, Kosmehl H, Lauer I, Nadrowitz R, Wedel T, Sieg P. A comparative study on the protection profile of lidocaine, amifostine, and pilocarpin on the parotid gland during radiotherapy. Cancer Res. 2005 Nov 15;65(22):10486-93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0023. PMID: 16288041.

- Lotz S, Caselitz J, Tschakert H, Rehpenning W, Seifert G. Radioprotection of minipig salivary glands by orciprenaline-carbachol. An ultrastructural and semiquantitative light microscopic study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1990;417(2):119-28. doi: 10.1007/BF02190529. PMID: 2114690.

- Guo L, Gao R, Xu J, Jin L, Cotrim AP, Yan X, Zheng C, Goldsmith CM, Shan Z, Hai B, Zhou J, Zhang C, Baum BJ, Wang S. AdLTR2EF1α-FGF2-mediated prevention of fractionated irradiation-induced salivary hypofunction in swine. Gene Ther. 2014 Oct;21(10):866-73. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.63. Epub 2014 Jul 17. PMID: 25030610.

- McDonald S, Meyerowitz C, Smudzin T, Rubin P. Preliminary results of a pilot study using WR-2721 before fractionated irradiation of the head and neck to reduce salivary gland dysfunction. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994 Jul 1;29(4):747-54. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90562-2. PMID: 8040020.

- Baum RP, Langbein T, Singh A, Shahinfar M, Schuchardt C, Volk GF, Kulkarni H. Injection of Botulinum Toxin for Preventing Salivary Gland Toxicity after PSMA Radioligand Therapy: an Empirical Proof of a Promising Concept. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018 Feb;52(1):80-81. doi: 10.1007/s13139-017-0508-3. Epub 2018 Jan 11. PMID: 29391917; PMCID: PMC5777965.

- Vacha P, Fehlauer F, Mahlmann B, Marx M, Hinke A, Sommer K, Richter E, Feyerabend T. Randomized phase III trial of postoperative radiochemotherapy +/- amifostine in head and neck cancer. Is there evidence for radioprotection? Strahlenther Onkol. 2003 Jun;179(6):385-9. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-1016-1. PMID: 12789464.

- Scrimger RA, Seikaly H, Vos LJ, Harris J, O'Connell D, Ghosh S, Debenham B, Jha N. Combination of submandibular salivary gland transfer and intensity-modulated radiotherapy to reduce dryness of mouth (xerostomia) in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2018 Nov;40(11):2353-2361. doi: 10.1002/hed.25339. Epub 2018 Sep 3. PMID: 30175876.

- Teng F, Fan W, Luo Y, Ju Z, Gong H, Ge R, Tong F, Zhang X, Ma L. Reducing Xerostomia by Comprehensive Protection of Salivary Glands in Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy with Helical Tomotherapy Technique for Head-and-Neck Cancer Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jul 14;2019:2401743. doi: 10.1155/2019/2401743. PMID: 31380414; PMCID: PMC6662416.

- Saito E, Watari I, Mizumachi-Kubono M, Hsu-Hayashi S, Ono T. Occlusional Modifications Reversibly Alter Aquaporin 5 Expression and Localization in Rat Salivary Glands. Front Physiol. 2020 Jun 10;11:528. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00528. PMID: 32587522; PMCID: PMC7298139.

- Liu X, Gong B, de Souza LB, Ong HL, Subedi KP, Cheng KT, Swaim W, Zheng C, Mori Y, Ambudkar IS. Radiation inhibits salivary gland function by promoting STIM1 cleavage by caspase-3 and loss of SOCE through a TRPM2-dependent pathway. Sci Signal. 2017 Jun 6;10(482):eaal4064. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aal4064. PMID: 28588080; PMCID: PMC5798857.

- Wang TS, Coppens I, Saorin A, Brady NR, Hamacher-Brady A. Endolysosomal Targeting of Mitochondria Is Integral to BAX-Mediated Mitochondrial Permeabilization during Apoptosis Signaling. Dev Cell. 2020 Jun 22;53(6):627-645.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.014. Epub 2020 Jun 5. PMID: 32504557; PMCID: PMC7433306.

- Marmary Y, Adar R, Gaska S, Wygoda A, Maly A, Cohen J, Eliashar R, Mizrachi L, Orfaig-Geva C, Baum BJ, Rose-John S, Galun E, Axelrod JH. Radiation-Induced Loss of Salivary Gland Function Is Driven by Cellular Senescence and Prevented by IL6 Modulation. Cancer Res. 2016 Mar 1;76(5):1170-80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1671. Epub 2016 Jan 12. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 2016 May 1;76(9):2846. PMID: 26759233.

- Adwan TS, Ohm AM, Jones DNM, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. Regulated binding of importin-α to protein kinase Cδ in response to apoptotic signals facilitates nuclear import. J Biol Chem. 2011 Oct 14;286(41):35716-35724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255950. Epub 2011 Aug 24. PMID: 21865164; PMCID: PMC3195609.

- van Dijk LV, Fuller CD. Artificial Intelligence and Radiomics in Head and Neck Cancer Care: Opportunities, Mechanics, and Challenges. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2021 Mar;41:1-11. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_320951. PMID: 33929877; PMCID: PMC8218312.

- Maleki F, Le WT, Sananmuang T, Kadoury S, Forghani R. Machine Learning Applications for Head and Neck Imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2020 Nov;30(4):517-529. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2020.08.003. PMID: 33039001.

- Chinnery T, Arifin A, Tay KY, Leung A, Nichols AC, Palma DA, Mattonen SA, Lang P. Utilizing Artificial Intelligence for Head and Neck Cancer Outcomes Prediction From Imaging. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2021 Feb;72(1):73-85. doi: 10.1177/0846537120942134. Epub 2020 Jul 31. PMID: 32735452.

- Mahmood H, Shaban M, Rajpoot N, Khurram SA. Artificial Intelligence-based methods in head and neck cancer diagnosis: an overview. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jun;124(12):1934-1940. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01386-x. Epub 2021 Apr 19. PMID: 33875821; PMCID: PMC8184820.

- Abdel Razek AAK, Khaled R, Helmy E, Naglah A, AbdelKhalek A, El-Baz A. Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning of Head and Neck Cancer. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2023 Feb;30(1):81-94. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2021.06.016. PMID: 34802583.