More Information

Submitted: January 09, 2026 | Approved: January 19, 2026 | Published: January 20, 2026

How to cite this article: Hillman AK, Ramis P, Nielsen P, Rohren EM. Return Visits after Breast Imaging Examination: A Multicenter Analysis of Patient Age, Modality, and Hospital Rating Factors. J Radiol Oncol. 2026; 10(1): 001-008. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jro.1001085

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jro.1001085

Copyright license: © 2026 Hillman AK, et al.. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Return visits for breast imaging examination; Hospital quality perception; Mammography; Breast ultrasound

Return Visits after Breast Imaging Examination: A Multicenter Analysis of Patient Age, Modality, and Hospital Rating Factors

Andrew K Hillman1, Phil Ramis2, Patrick Nielsen2 and Eric M Rohren2

1Baylor College of Medicine, Texas, USA

2Radiology Partners Research Institute, Tennessee, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Andrew Kwame Hillman, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas, USA, Email: [email protected]

Background: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores are used nationally to assess patient experience and hospital performance. Whether a higher overall hospital rating is associated with increased return visits to affiliated radiology centers remains unclear. Objective: To evaluate the likelihood of patients returning for additional breast imaging exams to the same hospital-affiliated imaging center, based on patient age & breast imaging exams received at the earliest visit, and the hospital’s HCAHPS patient satisfaction scores (overall hospital rating).

Method: We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from hospital-affiliated radiology centers between January 4, 2022, and December 31, 2023. Patient demographics, imaging encounter data, and return visit status were obtained from the medical records of imaging centers, each stationed at and affiliated with a hospital. The affiliated hospitals’ overall rating (linear mean scores) was also obtained. The primary outcome was the odds of return visits to the same imaging center for additional breast imaging exams-either follow up or unrelated. A multilevel logistic regression model, adjusting for patient- and hospital-level covariates, was used to assess the odds of patient return to the same imaging centers, by patient age & breast imaging exams received at the earliest visit, and the hospital’s HCAHPS overall rating. A second analysis was to determine the predicted probability of return based on the same factors.

Results: A mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to assess factors associated with return visits, while accounting for clustering at the hospital level. The analysis included 12,879 patient encounters across 18 imaging centers. After adjusting for relevant covariates, a higher overall hospital rating also showed a modest increase in return visit likelihood; however, it was statistically insignificant (OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.98–1.11, p = 0.203). Older age at earliest visit (OR = 1.012, 95% CI: 1.006–1.018, p < 0.001) was associated with a slight increase in odds of return visits. Compared to the reference group (patient who received only screening mammography at the earliest visit), patients had a significantly lower odds of returning for additional breast imaging if they had only diagnostic mammography exams (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.42, p < 0.001) or a combination of two breast imaging modality done on the same day at earliest (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.18–0.36, p < 0.001). Those imaged with only MRI of the breast on the earliest visit had a lower, but statistically insignificant odds of return for additional imaging (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.45–1.40, p = 0.418), compared to the reference group.

Conclusion: Hospitals with higher patient satisfaction scores demonstrated modestly increased but statistically insignificant odds of patient return to affiliated imaging centers. Older patients are also more likely to return to imaging centers for additional breast imaging exams than younger patients. Additionally, compared to patients who had only screening mammography at the earliest visit on their earliest visit, patients who had diagnostic mammography exams only, breast ultrasound only, breast MRI only, or a combination of two breast imaging modalities done on the same day on their earliest visit had lower odds of return visits for additional imaging. These findings support the potential downstream value of patient age, breast imaging modality, and hospital-level patient experience metrics in outpatient imaging services.

Patient case management and ensuring continuity of care are important parts of quality in diagnostic imaging services. This is especially true for breast imaging, where follow-up and repeat exams are often needed for effective screening, surveillance, and diagnosis. Understanding factors that influence patients’ return to the same radiology center for follow-up imaging can inform strategies for patient-centered care and improve patient outcomes.

Previous studies have shown that there is a substantial link between patient satisfaction and experience leading to willingness to utilize services again in the same healthcare facility, including radiology centers [1,2]. When it comes to breast imaging, both clinical and non-clinical factors, including trust in the imaging center, may play a significant role in deciding whether a patient would like to return to the same imaging center for follow-up care [3].

Patient age serves as an important variable in patient return behavior, as it frequently correlates with clinical indication, screening behavior, insurance type, and familiarity with healthcare systems [4]. For example, compared to older patients receiving routine mammography screening, younger women might have different reasons for follow-up or fewer imaging needs. Also, the type of breast imaging performed at the first visit—screening mammography, diagnostic mammography, ultrasound, or MRI—may represent distinct clinical pathways and affect the probability of a follow-up visit. Higher acuity or more complex care needs may be indicated by diagnostic or problem-solving modalities, which could potentially strengthen patients’ loyalty to a specific imaging facility.

Aside from patient and modality characteristics, retention may also be impacted by aspects of the healthcare system, such as the affiliated hospital’s overall quality rating. Patients are more likely to return to facilities affiliated with reputable, well-regarded, and highly rated institutions [5,6]. It has been demonstrated that several patient behaviors, such as the likelihood to recommend, trust, and return for subsequent evaluation, are correlated with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores, especially overall hospital ratings [2,6,7].

Despite the importance of these variables, a few studies have explored how patient-level factors (e.g., age, imaging modality) and institution-level factors (e.g., affiliated hospital’s rating) influence whether patients return for recommended follow-up visits to breast imaging centers. Our study aims to fill this gap by examining how the odds of returning for subsequent imaging evaluation are influenced by patient age, breast imaging modality at the earliest visit, and the overall rating of the affiliated hospital.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the electronic medical records (EMRs) of 18 hospital-affiliated radiology/imaging centers between January 4, 2022, and December 31, 2023. We focused on specific information from the data; this includes patient age, details of imaging encounter at the earliest visits (such as type of breast imaging study & date of visit, and the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category from each patient’s breast imaging results). Also, each hospital-affiliated imaging center was assigned its hospital’s overall rating as a proxy measure of the overall rating of the imaging centers. This information was used to determine the odds of patient return for additional breast imaging studies within the study period.

The hospital ratings were obtained from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, a standardized tool used to measure patients’ perceptions of their hospital experience, including communication with healthcare providers, staff responsiveness, cleanliness, and overall satisfaction. Publicly reported HCAHPS scores are typically based on rolling four-quarter periods of patient surveys into a single mean score. Each quality measure in these quarterly reports is reported either as a linear mean score (ranging from 0 to 100) or as a star rating (ranging from 1 to 5) [8]. The most current HCAHPS data used in the analysis covered the period from July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024 [9].

This study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board (IRB) review by the Baylor College of Medicine IRB.

Study variables

The primary predictor variables for this study are patient age at the earliest imaging visit, imaging modality at the earliest visit, and the affiliated hospital’s HCAHPS overall hospital rating. Patients who received two breast imaging modalities on the same day during their earliest visit were categorized as “two breast imaging modalities.” This category included combinations such as breast ultrasound and diagnostic mammography, breast ultrasound and breast MRI, or screening and diagnostic mammography. Patient-level covariate included in the analysis was the BI-RADS category from each patient’s earliest breast imaging study (BI-RADS categories 1 to 6). Patients were categorized as “unknown” if the breast imaging report did not include the BI-RADS category. This category includes patients receiving any of the following procedures: image-guided biopsies of breast tissues (wire localization biopsy, stereotactic guided biopsy), pre-surgical breast procedures (magnetic seed pellet placement, infrared activated electromagnetic reflector device placement), and post-mastectomy breast imaging.

Hospital-level covariates included each hospital’s location (rural versus urban), teaching status (teaching versus non-teaching), and total staff bed count. These were obtained from the American Hospital Directory and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) cost report (Hospital Provider Cost Report file) [10,11].

The outcome variable was return visit status. A patient was considered to have had a return visit if they had at least two visits to the same imaging center, with at least one of the visits occurring on a different date.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the patient’s odds of return for additional breast imaging exams following their earliest recorded imaging visit during the study period. To determine the odds of return visits, we employed a multilevel logistic regression model. This approach accounted for clustering of patients within hospitals and adjusted for both patient-level (BI-RADS category) and hospital-level covariates (hospitals’ location, teaching status, and total staff beds).

A secondary analysis was performed to estimate the adjusted probability of return visits as a result of patient age at the earliest visit, type of breast imaging received during the initial encounter, and the hospital’s overall rating. Marginal effects were computed and visualized to illustrate predicted probabilities across subgroups defined by these key variables.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 18.5 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) [12]. A two-sided p - value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study included 12,879 patients who underwent one or more breast imaging examinations over 24 months at hospital-affiliated imaging centers. Only 3.1% of patients (n = 397) had their earliest imaging visit occur outside the most recent HCAHPS rolling four-quarter survey period (July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024). Among these, the earliest visit date was approximately 1.5 years before the start of the survey period.

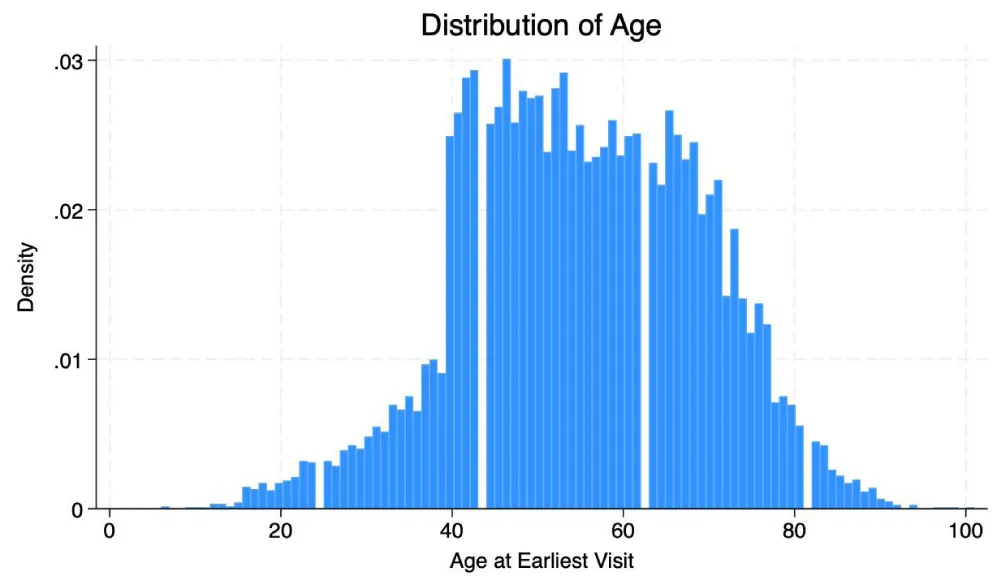

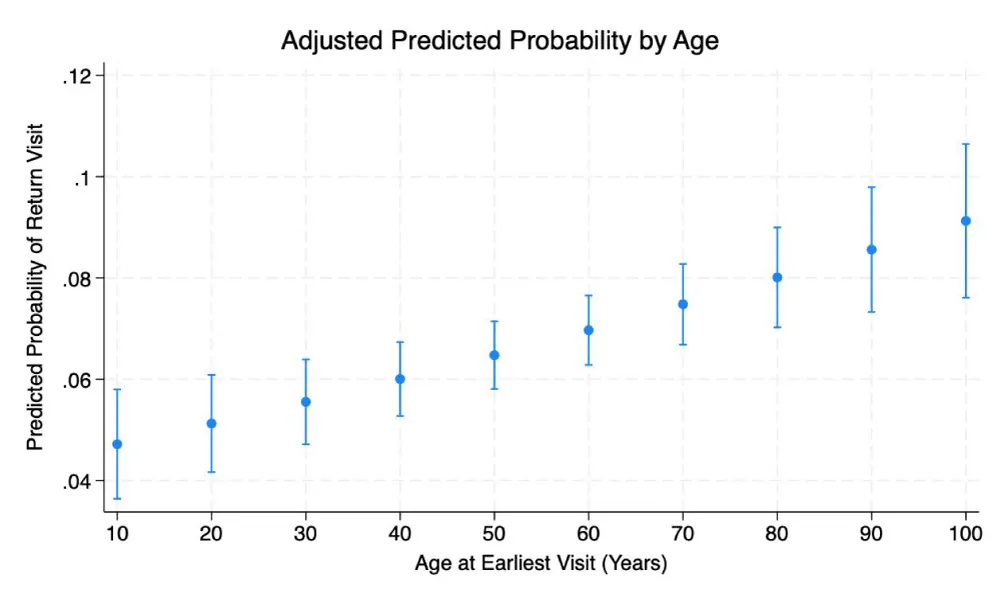

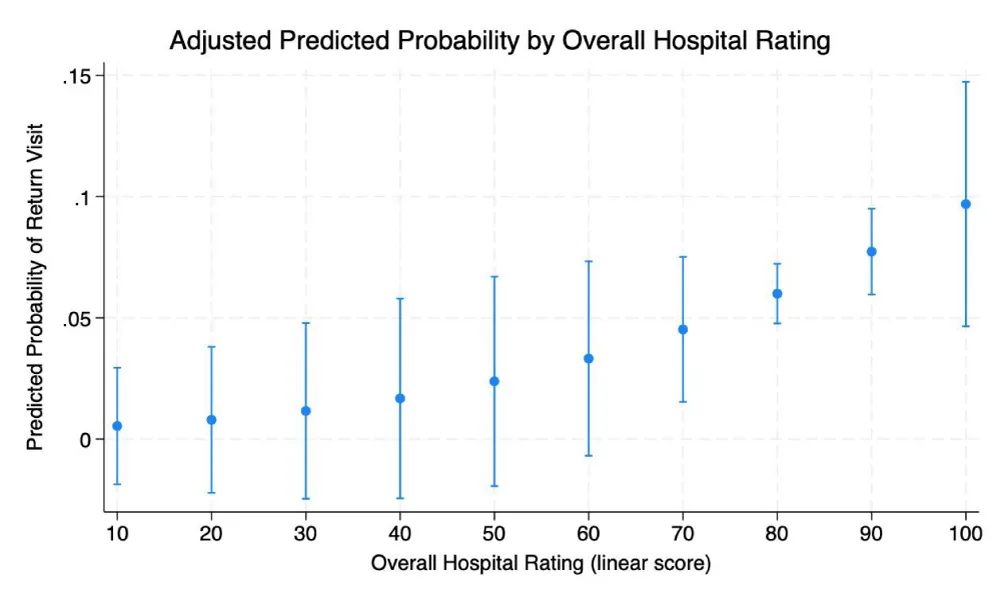

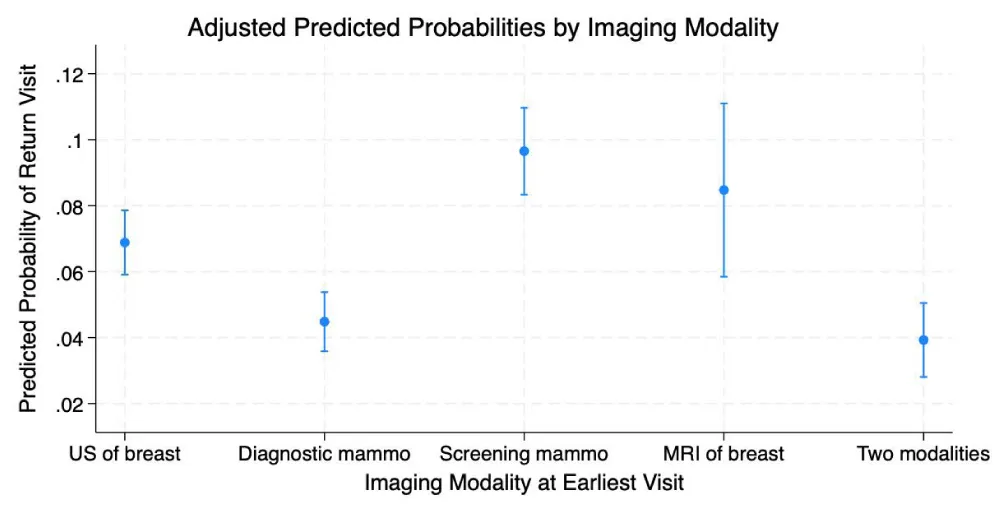

Table 1 presents a breakdown of patients by age, the type of breast imaging performed at their earliest visit, and BI-RADS category from earliest imaging reports, categorized by whether they returned for additional follow-up visits. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of patients by age. Table 2 is a summary of the 18 affiliated hospitals’ data that categorizes hospital location & teaching status, each hospital’s total staffed bed, and overall hospital rating (the hospitals are labeled H1 to H18). Table 3 displays the results of the mixed-effects logistic regression analysis, while Table 4 shows the adjusted probabilities of return visits based on patient age, imaging modality at the earliest visit, and the hospital’s overall rating. Figures 2-4 provide graphical representations of the adjusted probabilities of return visits.

| Table 1: Summary statistics of patient age and breast imaging modality type on the earliest visit by return visit status. | ||||

| Variable | Overall (N = 12,879) | Not Returned (N = 11,996) | Returned (N = 883) | p - value |

| Age on earliest visit, mean (SD) | 55.2 (13.9) | 55.1 (13.9) | 56.3 (13.6) | 0.0146 |

| Modality type during earliest visit n, (%) | ||||

| Ultrasound of the breast | 4751 (36.9) | 4,311 (35.9) | 440 (49.8) | <0.0001 |

| Diagnostic mammography | 1,315 (10.2) | 1,204 (10.0) | 111 (12.6) | |

| Screening mammography | 6,259 (48.6) | 6008 (50.1) | 251 (28.4) | |

| MRI of the breast | 183 (1.4) | 154 (1.3) | 29 (3.3) | |

| Two breast imaging modalities* | 371 (2.9) | 319 (2.7) | 52 (5.9) | |

| BI-RADS Category from imaging reports n, (%) | ||||

| 0 | 1,052 (8.2) | 720 (6.0) | 332 (37.6) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 4,032 (31.3) | 4,025 (33.6) | 7 (0.8) | |

| 2 | 5,578 (43.3) | 5,535 (46.1) | 43 (4.9) | |

| 3 | 811 (6.3) | 773 (6.4) | 38 (4.3) | |

| 4 | 800 (6.2) | 435 (3.6) | 365 (41.3) | |

| 5 | 83 (0.6) | 44 (0.4) | 39 (4.4) | |

| 6 | 281 (2.2) | 232 (1.9) | 49 (5.6) | |

| unknown | 242 (1.9) | 232 (1.9) | 10 (1.1) | |

| *Two breast imaging modalities can be either ultrasound of the breast and diagnostic mammography, ultrasound and MRI of the breast, or screening and diagnostic mammography. | ||||

| Table 2: Affiliated hospitals data summary. | ||||

| Hospital | Hospital location | Teaching hospital status | Hospital total staffed beds | Overall hospital rating - linear mean score |

| H1 | Urban | Teaching | 278 | 83 |

| H2 | Urban | Teaching | 569 | 84 |

| H3 | Urban | Teaching | 290 | 85 |

| H4 | Urban | Teaching | 611 | 80 |

| H5 | Urban | Teaching | 48 | 87 |

| H6 | Urban | Teaching | 241 | 84 |

| H7 | Urban | Teaching | 243 | 83 |

| H8 | Urban | Teaching | 252 | 83 |

| H9 | Urban | Non-Teaching | 53 | 84 |

| H10 | Urban | Teaching | 113 | 88 |

| H11 | Urban | Teaching | 356 | 78 |

| H12 | Urban | Teaching | 798 | 86 |

| H13 | Urban | Teaching | 184 | 87 |

| H14 | Urban | Teaching | 80 | 85 |

| H15 | Urban | Teaching | 178 | 86 |

| H16 | Urban | Teaching | 624 | 86 |

| H17 | Urban | Teaching | 91 | 84 |

| H18 | Rural | Non-Teaching | 49 | 87 |

| Table 3: Mixed-effects Logistic Regression Results. | |||

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p - value |

| HCAHPS Overall hospital rating (linear mean score) | 1.04 | 0.98 – 1.11 | 0.203 |

| Age at earliest visit | 1.012 | 1.006 – 1.018 | <0.001 |

| Imaging modality during the earliest visit | |||

| Ultrasound of the breast (vs. screening mammography) | 0.56 | 0.40 – 0.79 | 0.001 |

| Diagnostic mammography (vs. screening mammography) | 0.30 | 0.22 – 0.42 | <0.001 |

| MRI of breast (vs. screening mammography) | 0.79 | 0.45 – 1.40 | 0.418 |

| Two imaging modalities (vs. screening mammography) | 0.25 | 0.18 – 0.36 | <0.001 |

| BI-RADS Category (as documented earliest breast imaging report) | |||

| 1 (vs. 0) | 0.002 | 0.0009 – 0.0044 | <0.001 |

| 2 (vs. 0) | 0.013 | 0.009 – 0.018 | <0.001 |

| 3 (vs. 0) | 0.12 | 0.08 – 0.19 | <0.001 |

| 4 (vs. 0) | 2.02 | 1.46 – 2.80 | <0.001 |

| 5 (vs. 0) | 1.92 | 1.11 – 3.32 | 0.019 |

| 6 (vs. 0) | 0.59 | 0.39 – 0.90 | 0.013 |

| unknown (vs. 0) | 0.13 | 0.06 – 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Hospital location | |||

| Rural (vs. urban) | 0.32 | 0.11 – 0.94 | 0.038 |

| Teaching Status | |||

| Teaching (vs. non-teaching) | 0.54 | 0.27 – 1.08 | 0.082 |

| Hospital total staffed beds | 1.0008 | 1.00006 – 1.0015 | 0.003 |

| Random intercept variance | 0.068 | 0.018 – 0.256 | |

| HCAHPS: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. | |||

| Table 4: Adjusted Predicted Probabilities. | |||

| Overall Hospital Rating (linear mean score) |

Predicted Probability (%) | 95% CI (%) | p - value |

| 10 | 0.54% | [-1.87%, 2.94%] | 0.661 |

| 20 | 0.79% | [-2.22%, 3.80%] | 0.606 |

| 30 | 1.16% | [-2.46%, 4.78%] | 0.531 |

| 40 | 1.67% | [-2.44%, 5.79%] | 0.426 |

| 50 | 2.38% | [-1.93%, 6.70%] | 0.280 |

| 60 | 3.32% | [-0.69%, 7.33%] | 0.104 |

| 70 | 4.52% | [1.54%, 7.51%] | 0.003 |

| 80 | 6.00% | [4.76%, 7.23%] | <0.001 |

| 90 | 7.73% | [5.96%, 9.50%] | <0.001 |

| 100 | 9.69% | [4.65%, 14.73%] | <0.001 |

| Age at earliest visit | |||

| 10 | 4.71% | [3.64%, 5.80%] | <0.001 |

| 20 | 5.12% | [4.17%, 6.08%] | <0.001 |

| 30 | 5.56% | [4.71%, 6.39%] | <0.001 |

| 40 | 6.00% | [5.27%, 6.73%] | <0.001 |

| 50 | 6.47% | [5.80%, 7.14%] | <0.001 |

| 60 | 6.97% | [6.28%, 7.65%] | <0.001 |

| 70 | 7.48% | [6.68%, 8.28%] | <0.001 |

| 80 | 8.01% | [7.02%, 9.00%] | <0.001 |

| 90 | 8.56% | [7.32%, 9.79%] | <0.001 |

| 100 | 9.13% | [7.61%, 10.64%] | <0.001 |

| Modality at the earliest visit | |||

| Ultrasound of the breast | 6.89% | [5.90%, 7.85%] | <0.001 |

| Diagnostic mammography | 4.48% | [3.59%, 5.38%] | <0.001 |

| Screening mammography | 9.65% | [8.33%, 10.97%] | <0.001 |

| MRI of the breast | 8.47% | [5.84%, 11.10%] | <0.001 |

| Two breast imaging modalities | 3.92% | [2.80%, 5.05%] | <0.001 |

Figure 1: Distribution of patient age at earliest visit.

Figure 2: Advanced Adjusted predicted probability of patient return by age at earliest visit.

Figure 3: Adjusted predicted probability of patient return by overall hospital rating.

Figure 4: Adjusted predicted probability of patient return by imaging modality received at the earliest visit**. US of the breast: ultrasound of the breast; Diagnostic mammo: Diagnostic mammography; Screening mammo: Screening mammography; MRI of breast: Magnetic resonance imaging of breast.

The mean age at the earliest visit was 55.2 years (SD = 13.9). Nearly half of the patients (48.6%) received a screening mammogram at their earliest visit. In addition, 36.9% underwent a breast ultrasound, 10.2% had a diagnostic mammogram, 2.9% received two breast imaging modalities on the earliest visit, and 1.4% had a breast MRI at their earliest visit. About 99.2% of patients who were imaged with two breast imaging modalities had a combination of ultrasound of the breast and diagnostic mammography on the same earliest visit day. The rest had screening and diagnostic mammography (N = 2) and a combination of breast ultrasound and MRI (N = 1).

Approximately 8.2%, 31.3% 43.3%, 6.3%, 6.2% 0.6, and 2.2% were classified as BI-RADS categories 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively. Additionally, about 1.9% of patients had an unknown BI-RADS category; this group included individuals who received breast imaging services such as image-guided biopsy, pre-surgical breast procedures with imaging, and post-mastectomy breast imaging.

Results of mixed-effects logistic regression

A mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with patient return visits, while accounting for clustering at the hospital level. The model included 12,879 observations from 18 hospitals. The inclusion of a hospital-level random intercept significantly improved model fit compared to a standard logistic regression (LR test, χ² = 6.44, p = 0.0056). Our analysis focused on three predictors of return visit after initial imaging, adjusting for hospital total staffed bed: patient age at earliest visit, imaging modality at earliest visit, and hospital rating.

Older patients at the earliest visit have a slightly higher odds of a return visit (OR = 1.012, 95% CI: 1.006–1.018, p < 0.001). A higher overall hospital rating also showed a modest increase in the odds of return for additional breast imaging, although the effect was not statistically significant (OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.98–1.11, p = 0.203).

Imaging modality was a strong predictor of return visits. Compared to patient who had screening mammography alone at the earliest visit (the reference group), patients imaged using only ultrasound of the breast on earliest visit had significantly lower odds of returning for additional imaging (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.40–0.79, p = 0.001), whereas those imaged with only MRI of the breast on earliest visit had a lower, but statistically insignificant odds of return for additional imaging (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: 0.45–1.40, p = 0.418). Compared to those imaged with screening mammography at the earliest visit, patients had a significantly lower odds of returning for additional breast imaging if they had diagnostic mammography exams alone (OR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.42, p < 0.001) or a combination of two breast imaging modality done on the same day at earliest (OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.18–0.36, p < 0.001

Random intercept variance for hospitals was estimated at 0.068 (95% CI: 0.018–0.256), indicating modest variation in baseline return visit odds across facilities.

Predicted probabilities of return visits

The adjusted predicted probabilities for return visits increased steadily with patient age. For example, a 30-year-old had a 5.6% probability of return, compared to 7.0% at age 60 and 9.1% at age 100. This association was statistically significant across all ages (p < 0.001), reflecting a consistent age-related trend in return visits for breast imaging examinations.

A similar trend was observed for the overall hospital rating, although the association was only significant at higher rating levels. The predicted probability of return was negligible at lower ratings (e.g., 0.5% at a rating of 10, p = 0.661), but increased to 4.5% at a rating of 70 (p = 0.003) and peaked at 9.7% if hospitals were rated at 100 (p < 0.001). These results suggest that while age consistently predicts return visits, the effect of hospital quality perception may only emerge at very high satisfaction levels.

The adjusted predicted probability of return visits for additional breast imaging was 9.7% (p < 0.001) if the patient was imaged with screening mammography at the earliest visits. Those imaged with diagnostic mammography, MRI of the breast, and ultrasound of the breast at the earliest visit had an adjusted predicted probability of return visits of 4.5% (p < 0.001), 8.5% (p < 0.001), and 6.9% (p < 0.001), respectively. Those who had two breast imaging modalities on the earliest visit had an adjusted predicted probability of return visits of 3.9% (p < 0.001).

This study focused on how age at the earliest visit, imaging modality type, and the overall quality rating of the affiliated hospital affected patients’ likelihood of a returning visit for additional breast imaging workups. Our results highlight several significant patterns that contribute to the expanding body of research on patient behavior, care continuity, and the quality of the health system in diagnostic imaging.

Age and patient return

Patients who were older on their first visit were much more likely to return for follow-up imaging. This is consistent with earlier studies showing that older women are more likely than younger women to undergo routine screening for breast cancer and follow-up care [13,14]. The age-related difference could be due to higher awareness of breast cancer risk in older populations, more frequent clinical indications for imaging, or eligibility for Medicare coverage [15-17].

Furthermore, compared to younger patients, older patients may exhibit higher levels of loyalty to the health system or more consistent care-seeking behavior [18,19]. Since most breast cancer cases occur in older women, they are more likely to return to the same providers and imaging centers for follow-up after initial breast imaging examination. Also, frequent interactions with providers with each visit to the healthcare and imaging center foster and strengthen the patient-facility relationship, ensuring long-term continuity of care within the same facility.

Imaging modality and patient return

Our study results showed that, compared to patient that had a screening mammography alone at the earliest visit, those that only underwent only diagnostic mammography, ultrasound of the breast, or a combination of two breast imaging modalities (ultrasound of the breast and diagnostic mammography, ultrasound and MRI of the breast, or screening and diagnostic mammography) at the earliest visit had significantly lower odds of returning for additional breast imaging. Those who received MRI of the breast alone also had a lower (but not statistically significant) odds of return for additional follow-up breast imaging compared to screening mammography alone at the earliest visit.

Screening mammography recall rates appear higher than diagnostic mammography, with some evidence suggesting lower recall rates for ultrasound screening compared to mammography alone. Specifically, I. Tunçbilek, et al. found that diagnostic mammography and screening mammography have substantially different recall rates, with screening mammography having a 10.9% recall rate (for BI-RADS 0 assessment) [20]. A higher recall rate would mean that more additional tests (e.g., additional breast imaging and biopsies) would be required to further assess patients. Their study also showed that the diagnostic mammography group showed higher positive predictive values and cancer detection rates and lower recall rates compared to the screening mammography group [20]. E. Tohno, et al. demonstrated that combining mammography with ultrasound can actually reduce recall rates from 4.9% to 2.6% for screening examinations [21].

Contrary to our study findings, screening MRI of the breast consistently shows higher recall rates compared to screening mammography in high-risk women. R. Warren, et al. [22] demonstrated that recall rates for MRI of the breast was 10.19% while screening mammography recall rate was 4%. A comprehensive study by Glen Lo, et al. found MRI had a 23.3% recall rate compared to mammography’s 11.1% [23]. The higher recall rates correlate with MRI’s superior sensitivity in detecting potential abnormalities, though this comes with a trade-off of more false positives. The variability in recall rates suggests that precise figures can differ between screening centers and specific patient populations.

Hospital quality rating and patient return

Most significantly, we found that if the imaging center was connected to a hospital with a higher overall quality rating, patients were more likely to return for breast imaging. This result confirms earlier studies that found a relationship between patient trust, satisfaction, and loyalty and perceived institutional quality, as indicated by publicly available metrics like the HCAHPS overall rating [24,25]. Patient satisfaction is linked to patient loyalty, suggesting that satisfied patients are more likely to return to the same healthcare facility [26].

Patients facing sensitive diagnostic procedures like breast imaging often value hospitals with strong reputations—those known for great patient outcomes, clear communication, and dependable care [27,28]. Breast imaging can be emotionally stressful and frequently requires follow-up visits, especially when results are unclear or concerning. In these moments, patients often rely on a hospital’s reputation as a stand-in for the quality and safety they expect, which plays a big role in where they decide to go for follow-up care.

This connection between hospital ratings and patient return visits also reflects a larger shift in consumerism in healthcare and greatly influences health-seeking behavior, as patients turn to online reviews and publicly available hospital performance data to help them choose where to receive care [29]. For radiology practices that operate within or are closely affiliated with hospitals, this highlights the need to maintain a strong institutional reputation and provide consistently positive patient experiences to keep patients coming back.

Limitations of the study

HCAHPS patient survey scores reflect the inpatient experience. Patients receiving imaging services may be outpatients and are not influenced by inpatient care quality. Also, HCAHPS is at the hospital level, and return visits are at the patient level, leading to a mismatch in data granularity.

To accurately use HCAHPS survey data, patients’ visits must occur within the same timeframe. In this study, 3.1% of patients (n = 397) had their earliest imaging visit occur outside the most recent HCAHPS rolling four-quarter survey period (July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024). Although this is not a significant proportion of the data outside the HCAHPS survey period, it is a minor limitation that must be stated.

Another limitation is that patients were not all followed for the same period of time (e.g., all patients followed for 2 years regardless of earliest visit date), but rather the data used in this study analysis was only a snapshot of patients’ imaging records within specific dates. This means some patients recommended follow-up visits might have been missed as they occurred at a later date, not captured in the data.

The findings of our study may only apply to integrated systems where hospitals and imaging centers are closely affiliated. The generalizability of the findings might not apply to unaffiliated and stand-alone radiology centers.

In a future study, we aim to assess return visit behavior using patient satisfaction and experience scores obtained directly from radiology-specific patients. For instance, only those undergoing breast imaging exams in a radiology center. We would also adjust for other patient-level covariates if data is available (insured status, socioeconomic status, etc.) and other hospital-level covariates (e.g., total radiologists, total staff). The data will include patients followed for the same period of time. Analysis would also be restricted to only patients who required follow-up imaging visits based on recommendations from an earlier visit. This allows for a more appropriate measure of return rate.

Hospitals with higher overall patient satisfaction scores showed a modest increase, but statistically insignificant odds in patients’ return for additional follow-up or evaluation at affiliated imaging centers when needed.

Furthermore, increasing age is associated with a slightly increased likelihood of returning visits and loyalty to the imaging facility, as breast cancer risk increases with age. Additionally, compared to patients who had only screening mammography at the earliest visit on their earliest visit, patients who had diagnostic mammography exams only, breast ultrasound only, breast MRI only, or a combination of two breast imaging modalities done on the same day on their earliest visit had lower odds of return visits for additional imaging.

These findings support the potential downstream value of patient age, breast imaging modality, and hospital-level patient experience metrics in outpatient breast imaging services.

- Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513-559. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958

- Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient. 2014;7(3):235-241. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0060-5

- Sickles EA, Miglioretti DL, Ballard-Barbash R, Geller BM, Leung JW, Rosenberg RD, et al. Performance benchmarks for diagnostic mammography. Radiology. 2005;235(3):775-790. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2353040738

- White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, de Moor J, Doria-Rose PV, et al. Cancer screening test use—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(8):201-206. Published 2017 Mar 3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a1

- Woo S, Choi M. Medical service quality, patient satisfaction, and intent to revisit: case study of public hub hospitals in the Republic of Korea. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252241. Published 2021 Jun 28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252241

- Garman AN, Garcia J, Hargreaves M. Patient satisfaction as a predictor of return-to-provider behavior: analysis and assessment of financial implications. Qual Manag Health Care. 2004;13(1):75-80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00019514-200401000-00007

- Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Edwards CA, Hilborne LH. Components of care vary in importance for overall patient-reported experience by type of hospitalization. Med Care. 2009;47(8):842-849. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e318197b22a

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HCAHPS: patients’ perspectives of care survey. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality/initiatives/hospital-quality-initiative/hcahps-patients-perspectives-care-survey

- HCAHPS Online. Hcahpsonline.org. Published 2019 Sep 12. Available from: https://www.hcahpsonline.org/

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS data: hospital provider cost report. Available from: https://data.cms.gov/provider-compliance/cost-reports/hospital-provider-cost-report

- American Hospital Directory. Information about hospitals from public and private data sources, including MedPAR, OPPS, hospital cost reports, and other CMS files. Published 2019. Available from: https://www.ahd.com/

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 18.5. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2025.

- Sabatino SA, White MC, Thompson TD, Klabunde CN; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cancer screening test use—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):464-468. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25950253/

- Løberg M, Lousdal ML, Bretthauer M, Kalager M. Benefits and harms of mammography screening. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):63. Published 2015 May 1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z

- Zhao G, Okoro CA, Li J, Town M. Health insurance status and clinical cancer screenings among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(1):e11-e19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.08.024

- Ulcickas Yood M, McCarthy BD, Lee NC, Jacobsen G, Johnson CC. Patterns and characteristics of repeat mammography among women 50 years and older. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(7):595-599. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10428196/

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YC, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614. Correction in: JAMA. 2016 Apr 5;315(13):1406. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12783

- Rundle-Thiele S, Russell-Bennett R. Patient influences on satisfaction and loyalty for GP services. Health Mark Q. 2010;27(2):195-214. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/07359681003745162

- Carlin CS. Patient loyalty in a mature IDS market: is population health management worth it? Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):1011-1033. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12147

- Tunçbilek I, Ozdemir A, Gültekin S, Oğur T, Erman R, Yüce C. Clinical outcome assessment in mammography: an audit of 7,506 screening and diagnostic mammography examinations. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2007;13(4):183-187. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18092288/

- Tohno E, Umemoto T, Sasaki K, Morishima I, Ueno E. Effect of adding screening ultrasonography to screening mammography on patient recall and cancer detection rates: a retrospective study in Japan. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(8):1227-1230. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.02.007

- Warren RM, Pointon L, Caines R, Hayes C, Thompson D, Leach MO. What is the recall rate of breast MRI when used for screening asymptomatic women at high risk? Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20(7):557-565. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00535-0

- Lo G, Scaranelo AM, Aboras H, Ghai S, Kulkarni S, Fleming R, et al. Evaluation of the utility of screening mammography for high-risk women undergoing screening breast MR imaging. Radiology. 2017;285(1):36-43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017161103

- Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, Landon BE. The relationship between patients' perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(4):1024-1040. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01122.x

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa0804116

- Kessler DP, Mylod D. Does patient satisfaction affect patient loyalty? Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(4):266-273. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1108/09526861111125570

- Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201-203. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1211775

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. Published 2013 Jan 3. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/1/e001570

- Bardach NS, Asteria-Peñaloza R, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(3):194-202. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001360